What's the current status of regulated companies?

Since 2017 and the Sapin 2 law - and more specifically Article 17 thereof - large companies subject to this law have been obliged to set up an anti-corruption system or face financial penalties.

TheAFA (French Anti-Corruption Agency), in its role as supervisor, may at any time audit the company subject to the law to verify the means put in place according to the 8 fundamental pillars of the Sapin 2 law.

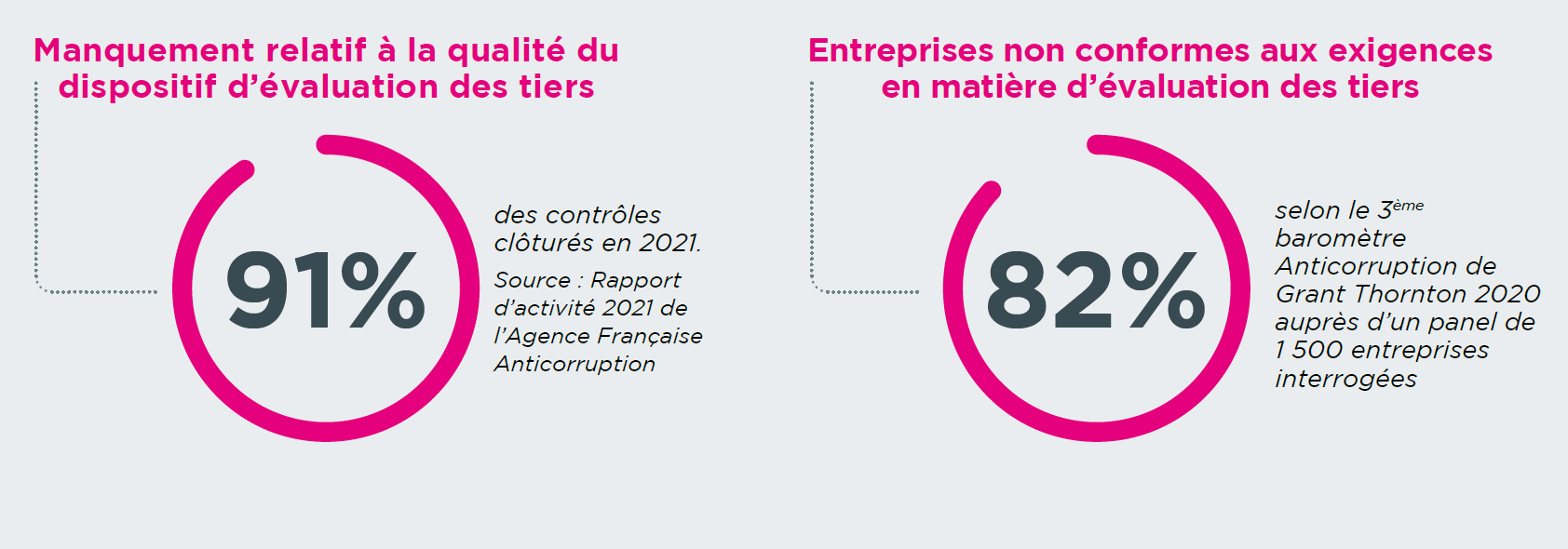

Initial audits and studies carried out by AFA have shown that it is extremely difficult to set up third-party assessments.

Three main reasons emerge from all the analyses carried out on the subject:

- The ability to gather all available data for due diligence purposes

- The number of third parties to be analyzed, often in different countries

- The multiplicity of players involved in the company and the "change" this requires

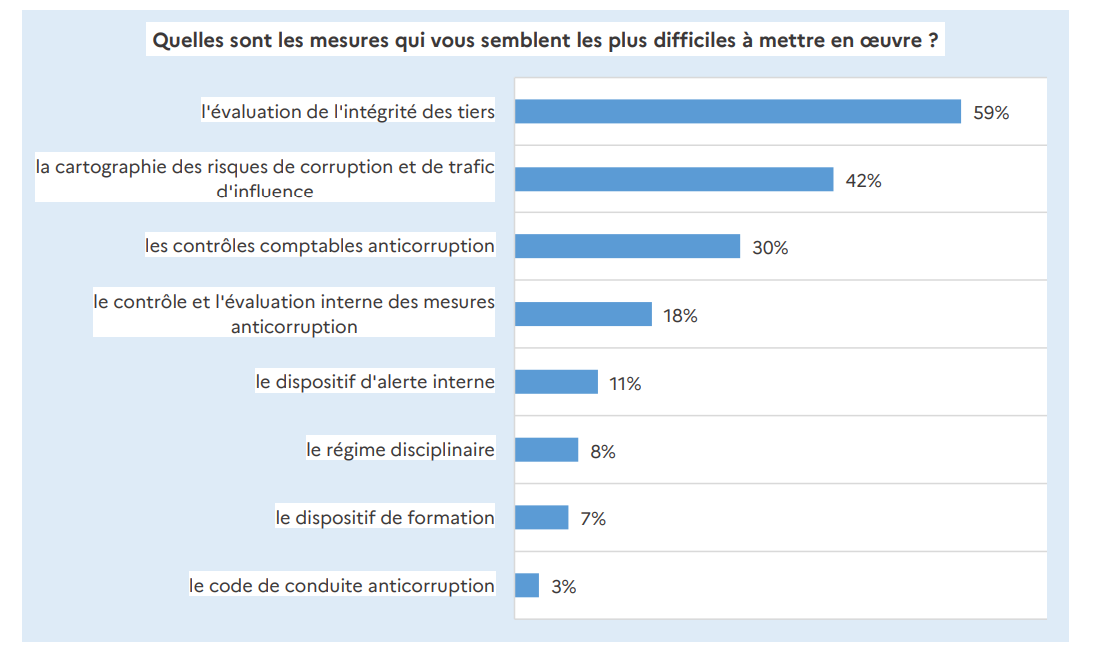

In this respect, the AFA's national diagnosis of anti-corruption arrangements published in September 2022 clearly shows that third-party assessment is judged by reporting entities to be the most difficult organization to implement.

This diagnosis is not surprising:

- Assessing the integrity of third parties is based on the mapping of corruption risks, which is also not so simple to implement, since it requires a collaborative, cross-functional approach involving the company's various functions (purchasing, sales, communications, etc.), under the supervision of the Compliance department and the impetus of general management.

- Assessing the integrity of third parties implies human action, which by definition cannot be fully automated in close proximity to operational responsibilities.

Change management at the heart of project success

The Cercle Montesquieu had already noted in September 2021 that more than half of compliance digitization projects focused on the single measure: assessing the integrity of third parties.

While the operationalization of third-party assessment requires digitalization to support the necessary aggregation of data on companies (legal entities) and their managers (natural persons) for a very large volume of French and international third parties, the difficulty lies mainly in the company's ability to adopt a new organization with operational staff in compliance with regulations.

If the company and its management are convinced of the benefits of implementing an anti-corruption system (as a minimum condition for success), the operational staff in charge of the assessment may legitimately perceive more of a constraint than a benefit in the performance of their duties.

This is the hallmark of any transformation project, which means communicating the meaning of the project to all employees, and in particular to those who will be in charge of evaluation: here, we need to make clear not only the financial risk, but also the reputational risk for the company. Indeed, employees increasingly want to work for a virtuous company that contributes to a sustainable economy.

Compliance issues better understood and adopted

Gradually, the perception of Compliance within the company is changing. Regulations are gradually moving from the "suffered" state to a "chosen" and "understood" mode.

Indeed, under the impetus of the European Union's Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), as part of the drive towards a sustainable economy, the evaluation of third parties should be carried out not only from an ethical angle, but also from an environmental, social and societal one.

Each assessor then becomes a link in the chain that gradually makes the economy virtuous, favoring third parties who implement solid Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) policies. More than just a link in the chain, the assessor becomes a real player in his or her company, capable of judging the relevance or otherwise of continuing a relationship with a supplier, intermediary or customer. By empowering the person carrying out the due diligence, managers can help to build loyalty among their staff.

This is particularly true if, in the future, third parties are to be assessed from a number of different angles: anti-corruption, social, societal, governance, environmental, cyber... It's easy to see that the first challenge will be to provide teams with as much qualified data on third parties as possible, and to offer them a secure process to guide them, even if not all team members are compliance experts. Employees should also be offered support from a specialized compliance team or from their superiors, and lastly, action should be focused on the RTGs (Third-Party Risk Groups) identified by the company's risk mapping.

Essential cost control

To be adopted, the solution will have to enable us to carry out qualitative, regulatory-compliant assessments in the shortest possible time.

The main cost for a company is therefore not the purchase price of the chosen solution, but the human cost of assessment. This internal workload can certainly be concentrated within a Compliance team. However, given the great diversity of third parties and the responsibility of organizations, in large companies this burden is increasingly spread over a large number of operational staff.

This hidden cost is far greater than the price of the digital solution, since it includes the training required to adopt the solution, support and the actual cost of due diligence. In addition to the resistance to change, which can prove costly, the most crucial challenge is to get the teams in charge of due diligence on board throughout the deployment of the solution, relying on referent promoters. Too often, a company's haste in the face of an AFA inspection can itself generate internal obstacles, whereas a gradual roll-out would allow a natural self-cultivation to compliance.

So, six years after the implementation of the Sapin 2 Act and its Article 17, how can we make life easier for ETIs and companies that are obliged to set up a third-party assessment measure in terms of integrity and tomorrow's social, societal, governance and environmental issues?